All is not as it seems

4 Dec 2017 by Evoluted New Media

Digital images are frequently used to provide supporting evidence within papers and reports, yet are not routinely submitted to any scientific process of authentication. In a world in which the tools to digitally manipulate an image are freely available, it’s no longer acceptable to simply take these images at face value says Martino Jerian

The past 12 months has seen the scientific community rocked by a series of scandals relating to the use of manipulated images within published scientific research.

In June this year the Leibniz Association reprimanded the research group of Karl Lenhard Rudolph, director of the Fritz-Lipmann-Institute of the Leibniz Society after identifying eight high-impact papers that contained manipulated images.[1] His institute is now banned from receiving Leibniz funding for three years.

Meanwhile, in Italy an investigation remains on going into whether the prominent cancer scientist Alfredo Fusco hired a photo studio to manipulate images that appeared in dozens of published papers.[2] The public prosecutor has already stated “it is clear that some images have been manipulated” and is currently deciding whether or not to press charges. Finally, in an alarming statistic that demonstrates just how widespread this practice may have become, the EMBO Journal has told Nature it finds evidence of image manipulation in 20% of papers accepted for publication.[3]

Researchers’ ambition to gain scientific exposure, to achieve career advancement or to secure funding, can drive them to embellish their results in order to attain their goals in the increasingly competitive world of scientific discovery. Equally the pressure to publish can see them stumbled across doctored images and incorporate them by mistake. In these cases, not only is the individual’s reputation at risk, but also their colleagues’ who are oblivious to the altered nature of the images. The impact of these images is extensive and far-reaching: they threaten to endanger the name of the organisation for which the researcher is working, as well as calling into question the integrity of the scientific community at large. This is a critical issue in the current technological day and age, yet very little is being done to address it. Bearing in mind the damage that doctored images can do, scientific publishers and research institutes ought to be more rigorous when setting out the requirements for images that are used in papers. After all, it should not be that difficult to stipulate complete transparency, especially considering that there are several guidelines available, such as those from the US National Institute of Health.[4]

Slice and dice

For individual researchers, reputation is everything. So, how do you go about protecting your reputation and establishing this transparency? A good rule of thumb is to always have the original image saved, so that you are able to produce it if questioned. Generally speaking, minor edits such as cropping out irrelevant parts of the image or resizing it are acceptable – but this may vary depending on the context.It becomes trickier when there is a need to validate images from third party sources, whether that is from internal colleagues or external laboratories. This requires access to specialist software and training. Although for general photography there are many tools available, for scientific images the usable toolset is distinctly more limited, depending on the image type and content. For example, in normal photos, we have many colours, shadows and 3D information. However, in scientific images, we very often only have planar information, no colour and a uniform background.

The two principal issues that we face are usually from local image manipulation, such as slicing (inserting a portion of another image) or cloning (copying a portion from within the same image).

If the alleged originals are available, then we need to verify that these actually are the originals. So, how can we do that? Ideally, if we are able to access the imaging device (digital microscope, camera, scanner, etc.) then we can create a test image and then verify if the format of the suspicious images matches the ones produced for the test.

Even if this option isn’t possible, this kind of analysis can still prove very helpful in determining whether an image is altered or not by checking for traces of image manipulation software. Imaging devices utilize formats in a different way to typical image processing software, which usually leaves clear traces of manipulation. If such traces are found, then the supposed originals are in fact not originals at all.

For example…

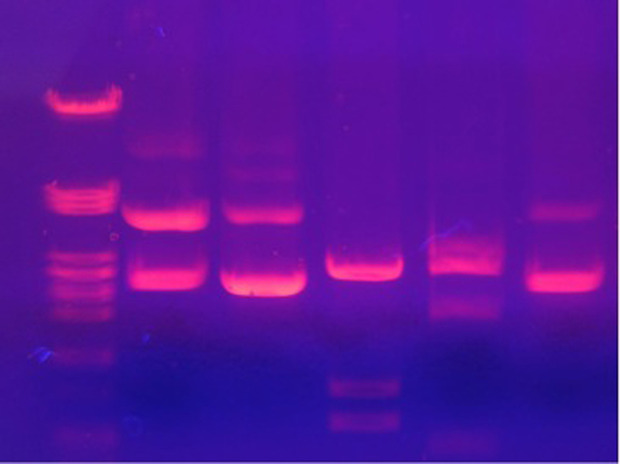

Let’s take a look now at a simulated example, using a common image in scientific papers, related to a process called electrophoresis.[caption id="attachment_64719" align="alignnone" width="200"] Can you spot anything wrong with this image? If you’re a professional in this field, and you know what this data represents, then you may be able to identify something. If not, however, it is very difficult to identify any issues by only looking at the image. But, if we use software specifically developed for detecting image tampering then we can begin to look at the image metadata where we find clear signs of Adobe Photoshop.[/caption]

Can you spot anything wrong with this image? If you’re a professional in this field, and you know what this data represents, then you may be able to identify something. If not, however, it is very difficult to identify any issues by only looking at the image. But, if we use software specifically developed for detecting image tampering then we can begin to look at the image metadata where we find clear signs of Adobe Photoshop.[/caption]

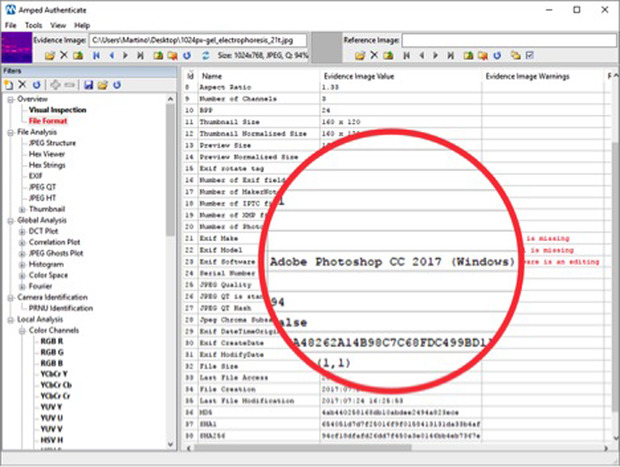

[caption id="attachment_64720" align="alignnone" width="200"] In some cases Photoshop may only have been used to resize the image, which can be considered justified. However, it serves as a red flag worthy of further investigation[/caption]

In some cases Photoshop may only have been used to resize the image, which can be considered justified. However, it serves as a red flag worthy of further investigation[/caption]

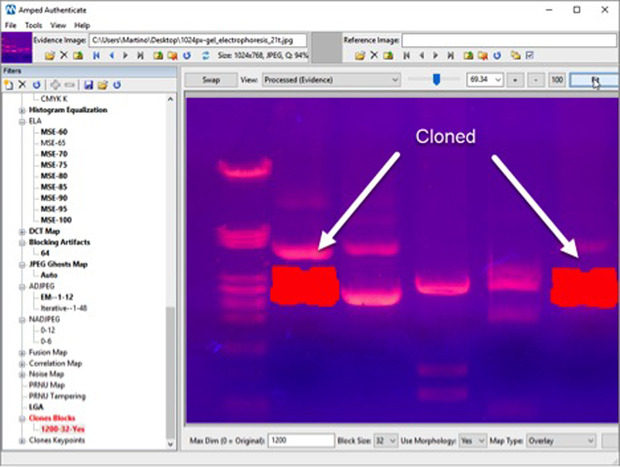

[caption id="attachment_64721" align="alignnone" width="200"] This is telling us that one part of the image has been cloned onto the other. But how can we tell which side has been copied onto the other? Inconsistencies in the compression history of the image can indicate which part of the image is suspicious and this can be confirmed by other industry-standard methodologies such as ELA (Error Level Analysis).[/caption]

This is telling us that one part of the image has been cloned onto the other. But how can we tell which side has been copied onto the other? Inconsistencies in the compression history of the image can indicate which part of the image is suspicious and this can be confirmed by other industry-standard methodologies such as ELA (Error Level Analysis).[/caption]

So, essentially, what has happened is that detail of the right hand part of the image has been copied and pasted to the left. Here you can see a comparison between the analysed image and the actual original, with the modified part.

In this example, we have found that the tampering – even if almost impossible to distinguish with the naked eye – can be easily identified and confirmed with multiple image analysis tools. In this case, the identification is possible because we have the good fortune to work with a high-quality JPEG image. However, if all we had was a low-resolution picture that had been embedded and recompressed into a PDF, then the odds of success would have been much lower.

For this reason, whenever possible these methods should be applied to the purported originals provided by the researchers, and the images embedded in the articles themselves should be used only as the last resort. It is in a scientist’s best interest to protect their own reputation by making the original files available. Therefore a refusal to do so – which goes against the scientific principle of accuracy, repeatability and reproducibility – could in certain circumstances present grounds for suspicion on its own.

A position of authenticity

There is another vital aspect that must be highlighted: with this kind of analysis it is very difficult to guarantee the authenticity of the image; on the other hand, if we can find traces of manipulation then we can be quite certain something about that image may require further investigation. If we fail to find any trace, it could be because the picture is actually authentic, or possibly because the image quality is so low that even traces of tampering are lost.If some basic screening were applied more extensively to scientific publications, with minimal effort we would be in a much better position to guarantee, or dispute, the authenticity of images within scientific papers for the benefit of science and its wider community.

Working to detect image manipulation in the world of science is a long-term battle, just as it is in photojournalism, forensics, and in any other field where image manipulation is a growing threat to the veracity of images.

References:

- https://www.nature.com/news/researchers-frustrated-by-italian-misconduct-probe-1.21923

- https://www.nature.com/news/image-doctoring-must-be-halted-1.22202

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4114110/

The Author:

Martino Jerian is CEO and Founder of Amped Software